There’s many different ways to communicate your thoughts to an audience. Going with a different approach leads to a different outcome: each medium has its own strengths and weaknesses. “The medium is the message” after all, as famous communication researcher Marshall McLuhan would say. In this post, we discuss the strengths of the written word.

Endless possibilities

There’s many different ways in which we can write a text. We can categorize these into three main branches:

- Narrative texts to tell a story and entertain, such as fantasy novels, play scripts and fairytales

- Expository texts for explaining complex topics and facts, such as scientific writing, textbooks, news articles and instruction manuals

- Argumentative texts to convince the reader of something, such as essays, propaganda and advertisements

Whatever the type, there’s many strengths to text.

Back to basics?

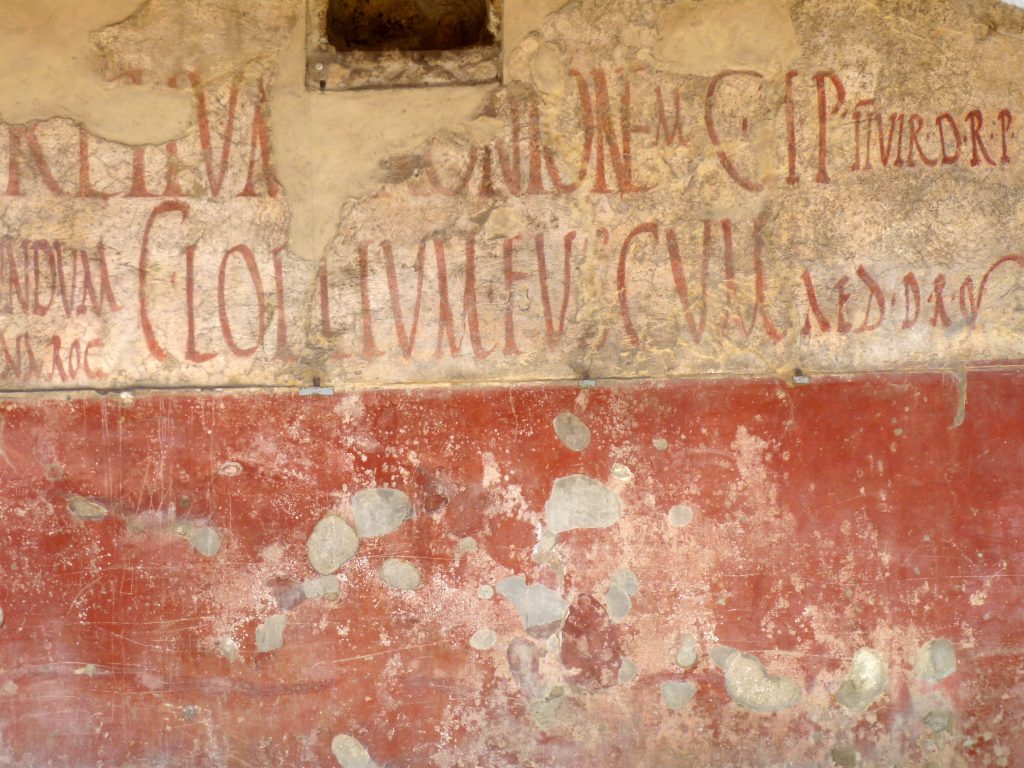

The written word has been around for an undeniable long time. Researchers believe that it goes as far back as 3400 B.C., when the Mesopotamians in what is now Iraq started using cuneiform script to log information. Over time, print has remained one of the key ways in which humans save information and convey their thoughts. With the arrival of the printing press in approximately 1440, the written word became a booming business – and it has remained so ever since.

However, printing text is not your only possibility. Text can come in many physical shapes: it can be handwritten, printed on paper or online, as a graffiti or even stamped into sand at a beach. It is an ever evolving medium, taking new shapes throughout time. With the arrival of the world wide web, we might even be writing and reading more than ever! Or is everything going towards videos? This flexibility is a major strength of text: you can choose whatever form of text you want in order to convey your message in the desired way.

Source of information

From a historic point of view, the choice for text might be a bit controversial: after all, large shares of populations were illiterate throughout history. So why did the literate still feel motivated to write? When we consider the purposes for which our ancestors would write, topics such as religion, economics and historiography come to mind. These are not the simplest of subjects, and in order to capture them in the right way, lots of information is needed.

Text, in comparison to images or statues, has the possibility to contain much more information. This makes for a more precise final product. Arguably, this is still the case: texts can be read quickly while conveying enormous amounts of information. And of course “knowledge is power” – a lot of literate people, usually people in power or of some higher rank in society, simply didn’t want the mob to know about what they wanted to communicate.

Staying true to your thoughts

Another upside of text, in our opinion, is that it’s malleable compared to other media. While of course, video and audio have the opportunity to make edits, it’s not as easy as going through your text editor and perfecting the text where needed. This process of revising your work makes for greater accuracy in conveying your thoughts. That’s perfect for when you’re writing along as you are developing your thoughts – for instance when you are working on an essay.

Adding insights

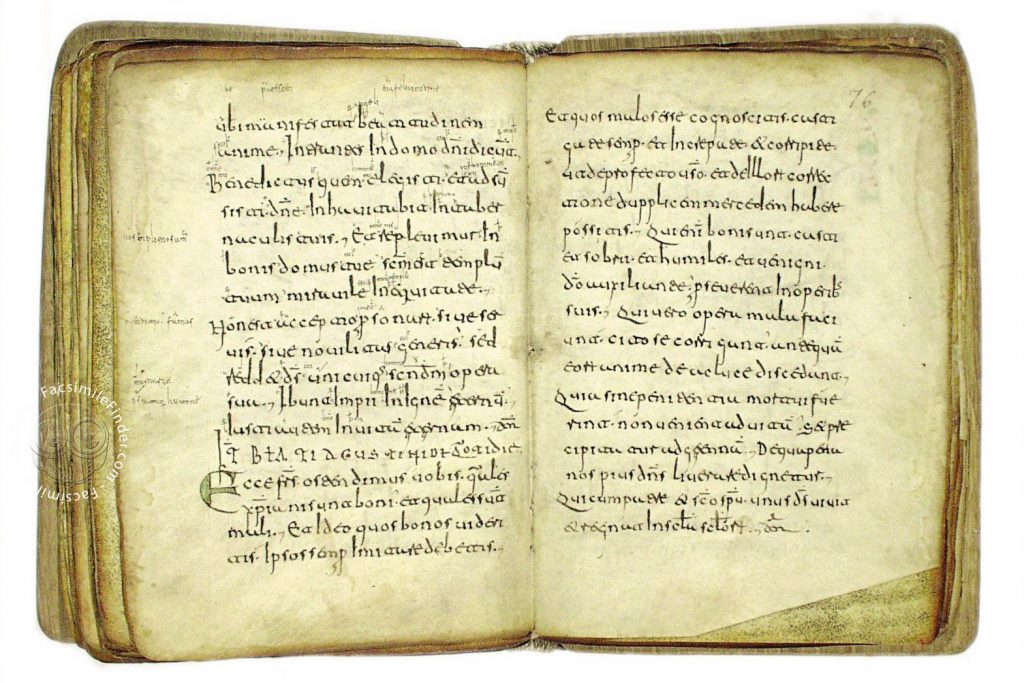

The ability to edit texts easily is also a perk for the reader of your text. With written information, you can go ahead and make adaptations where necessary. Making notes between the lines is not a possibility with other types of media. Texts that you read on the computer are easily saved and appended in a text editor, for instance, while that’s not so easily done with a video.

The concept of taking written work and making adaptations to it has been around for centuries, as some marginalia – notes made in the margins of documents – prove. Such notes are commonly made for improving the understanding of future readers. The Glosas Emilianenses are a centuries old example of marginalia, having been written in the 10th or 11th century in a Latin document that was over a hundred years old by then. While some notes are on grammar, others are additions or clarifications of the texts. Although much is unknown, the author was supposedly a Spanish monk which researchers have nicknamed ‘the upper one’.

A famous fictional example of marginalia also exists. In Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, the wizard is in need of a book for his potions class with professor Slughorn. Finding an old copy with annotations on the classroom bookshelf, he begins to perform very successfully in the challenging class. It is only later that he finds out who the person that previously owned the book is: the Half-Blood Prince, or professor Snape.

A lasting record

That we know when written text started in human history, is based on the fact that those texts still exist in a physical form. Take the Ebla tablets, a collection of around 1800 complete clay tablets, for instance. Many of these tablets focus on the economics of the city Ebla in what is now Syria: they sum up inventories of commercial relations as well as import and export activities. Writing provides us with a lasting record of information.

That’s great, because spoken language has much larger memory demands than written text: we can go back to read it whenever we want quickly.

Trust issues

… or not! We can put an uncountable amount of letters on paper, but if no one believes it, there’s no point in making the effort of choosing this medium. You don’t have to fret about that, however. While results vary per country and even within countries, research seems to point to a high credibility of text, be it in print or online.

Having the reader trust you on your word is, of course, more than important. That’s the case in particular for convincing someone of your thoughts. Here, framing comes into play. Framing theory, a concept which emerged in the previous century to persuade others, has been examined by many researchers. Social scientists Scheufele and Iyengar describe it as “a dynamic, circumstantially bound process of opinion formation in which the prevailing modes of presentation in elite rhetoric and news media coverage shape mass opinion.” By choosing certain words and phrases in our communication, we can emphasize our way of thinking. We do this both consciously and unconsciously. Through framing your message in the right way, you can move mountains.

sources

- https://www.piworld.com/article/survey-shows-paper-preferred-for-information-credibility-reading-pleasure/

- https://canvas.instructure.com/courses/31465/pages/advantages-and-limitations-of-intructional-media

- https://www.bl.uk/history-of-writing/articles/where-did-writing-begin#

- https://www.theguardian.com/media/2012/jun/03/who-says-print-is-dead

- Abdulla, R. A., Garrison, B., Salwen, M., Driscoll, P., & Casey, D. (2002, August). The credibility of newspapers, television news, and online news. In Education in Journalism Annual Convention, Florida USA.

- Scheufele, D. A., & Iyengar, S. (2012). The state of framing research: A call for new directions. The Oxford handbook of political communication theories, 1-26.

Header image: Yannick Pulver