We all have cognitive biases. Here at Kontextlab we might have a key to overcoming at least some of them. Got a gist? Let us put our finger on it. Just ponder for a second how the information spreading and new perspectives of mappings might turn things upside down.

What is a cognitive bias, anyways? It’s a systematic error that we make in our mind sometimes. It occurs when we are processing and interpreting information, in turn changing the decisions and judgements we make.

A ton of different cognitive biases exist. They come to us for instance through not paying attention well enough, or because we rely on memories. Or because we handle our information selectively, and choose to ignore some parts. Or because our emotions come into play. And that is totally normal, there are just too many bits of information incoming so we humans have to filter.

Most of these filters are really old – they developed when we had to flee from tigers and collect food ourselves, living in small groups wandering the world. However nowadays those once helpful filter techniques hinder us in making sound decisions.

While we can work to become aware of our own and other people’s biases so we can fight against it, they sometimes can ‘creep in’.

Systems of thinking

How do they creep in, then? Part of that is systems thinking. Systems thinking is a way of making sense of the complexity of the world by looking at it in terms of wholes and relationships rather than by splitting it down into its parts. Perhaps this quote of the Harvard Business Review explains it best:

“It can be dangerous to rely too heavily on what experts call System 1 thinking—automatic judgments that stem from associations stored in memory—instead of logically working through the information that’s available. No doubt, System 1 is critical to survival. It’s what makes you swerve to avoid a car accident. But as the psychologist Daniel Kahneman has shown, it’s also a common source of bias that can result in poor decision making, because our intuitions frequently lead us astray.

Other sources of bias involve flawed System 2 thinking—essentially, deliberate reasoning gone awry. Cognitive limitations or laziness, for example, might cause people to focus intently on the wrong things or fail to seek out relevant information.”

See? While system 1 is our quick-thinking-system, System 2 thinking is slower and requires more effort. It is conscious and logical. Going through system 1, which is what we do very, very often, might help cognitive biases to have a field day.

Brain (re)routing

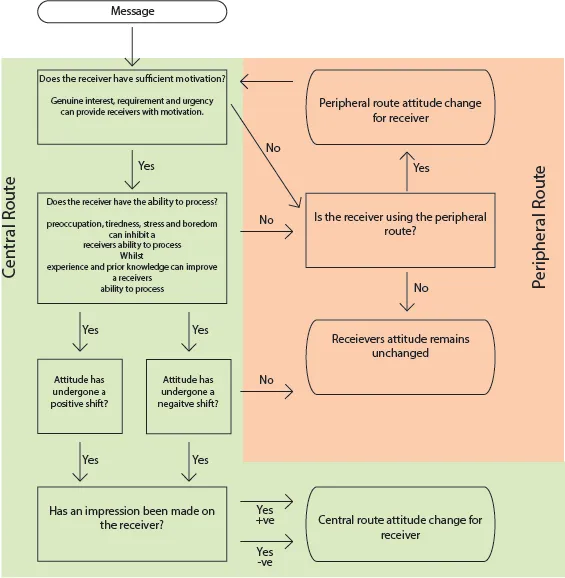

In similar fashion, there’s the Elaboration Likelihood Model. This dual process theory describes the change of attitudes and was developed by professors Richard E. Petty and John Cacioppo in 1980.

The model aims to explain different ways of processing stimuli. They affect the decisions we make. The model includes a ‘central route’ and a ‘peripheral route’. Under the first one, we carefully assess the information and arguments that we have available to us.

On the other hand, in the other route we’re using cues around us to positively or negatively affect our decisions. How attractive is the person telling us the information? Do they look credible and kind? Using this route is full of cognitive biases and might be triggered for instance by disinterest, tiredness or stress.

Overcoming the bias

That’s the issue right there: we might not always have the energy and attention to overcome our cognitive biases. However, there’s several things we cóuld do to fight the struggle. Here’s 8 (!).

- Practicing awareness

We should all know that we have biases in order to keep in mind that sometimes, our brains are plain wrong. - Factors

Considering all the factors at play can help you notice biases you may or may not have. Are you ignoring information? Are you feeling way too confident about your choice? - Looking for patterns

How did similar situations look in the past? No matter what, no situation is ever exactly the same. You can’t just use prior experience to conclude what will happen now. - Curiosity

Being curious can help you avoid cognitive biases: pause and think if you’ve explored everything. - Focus on growing

Yes, we do all make mistakes once in a while. But don’t let it get you down! It’s a chance to learn and keep your mindset positive. - Seek discomfort

What makes you uncomfortable? Identify it, and see if it’s affecting your choices somehow.

The guys behind YouTube account Yes Theory’s Seek Discomfort truly know where it’s at in that sense. This ‘community of dreamers who believe the best things in life exist outside the comfort zone’ helps you step out of your biases by getting to know the world around you better. - From the other side

Put yourself in the other’s shoes, or in opposite situations anyhow. A little empathy now and then goes a long way in overcoming cognitive biases. What’s their perspective? - Intellectual humility

Consider that there will always be someone who knows more about something than you do. ‘Intellectual humility’, as it’s called, should be practiced at all times!

As we promised in the intro already, though, we think there’s another option to overcome cognitive biases. Making a mapping of your thought process, chunks of information or choice process! Mappings filled with information and all kinds of wonderful perspectives might turn cognitive biases upside down.

What biases could they help with? Let’s have a look.

Anchoring bias

The so-called anchoring bias is a cognitive bias that causes us to rely too heavily on the first piece of information we are given about a topic. When we are setting plans or making estimates about something, we interpret newer information from the reference point of our anchor, instead of seeing it objectively. This can skew our judgment, and prevent us from updating our plans or predictions as much as we should.

The mappings, however, do help seeing the information more objectively and removes the aspect of ‘time’ in the situation: you’ve put all the information together, accessible at the same point in time.

Confirmation bias and conservatism bias.

The prior is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that confirms or supports one’s prior beliefs or values. The latter is the tendency to revise one’s belief insufficiently when presented with new evidence.

However, in a map several pieces of information are put together. While some might be confirming prior beliefs, others might not. But, since they are logically linked to one another, the biases can be taken away.

Ostrich effect

You might have suspected that ostriches would somehow come into play in this blog post – after all, just glimpse at the header picture. There’s a good reason for the birds up there: one cognitive bias is linked directly to them. It’s called the ‘ostrich effect’, in which individuals figuratively put their heads in the sand and avoid information they believe may be unpleasant.

The map helps put things in perspective and shows you a side to the coin that you might not have considered before, simply because you would rather not see it.

On a side note, ostriches don’t really stick their head in the sand to unsee scary or other unwanted things. They do so to rotate their eggs buried in the ground! In that way, moms ensure their babies are evenly heated in their temporary shells.

Salience and selective perception

The prior is the tendency to focus on the most easily recognizable features of a person or concept. The latter is allowing our expectations to influence how we perceive the world. Perceive what you want in media messages while ignoring opposing viewpoints.

The map, however, doesn’t attribute salience to information, but instead creates perspective and balances out knowledge and viewpoints.

Sources

- 20 Cognitive Biases That Screw Up Your Decisions

- List of cognitive biases

- Do ostriches really bury their head in the sand?

- What Is Cognitive Bias?

- Outsmart Your Own Biases

- Cognitive Bias: What It Is and How to Overcome It

- Elaboration likelihood model

Header image: elCarito