“Those who live by conspiracy theories die by them”, is what The Independent wrote about neo conceptual artist Mark Lombardi’s death in 2000. In March of that year, the American famous for creating mappings documenting alleged frauds, took his own life in his Brooklyn apartment.

However, as The Independent suggests, Lombardi’s death is clouded in conspiracies. Did the 48-year-old really commit suicide? Or was he perhaps prosecuted by the people whose secrets he revealed through his artwork?

We’re not a detective agency, so we will never know. One thing is clear however: Lombardi’s intensely complex mappings got attention from the ones he was publishing about, such as the Bush family. With his uncovering work, he might have risked it all.

His suicide, by hanging himself, is surrounded by some controversies. The time of death, for instance, was never established. Additionally, the verdict of suicide was based on a testimony of a unreliable witness. Lombardi also had no clinical history of depression.

Catching the eye of the secret service

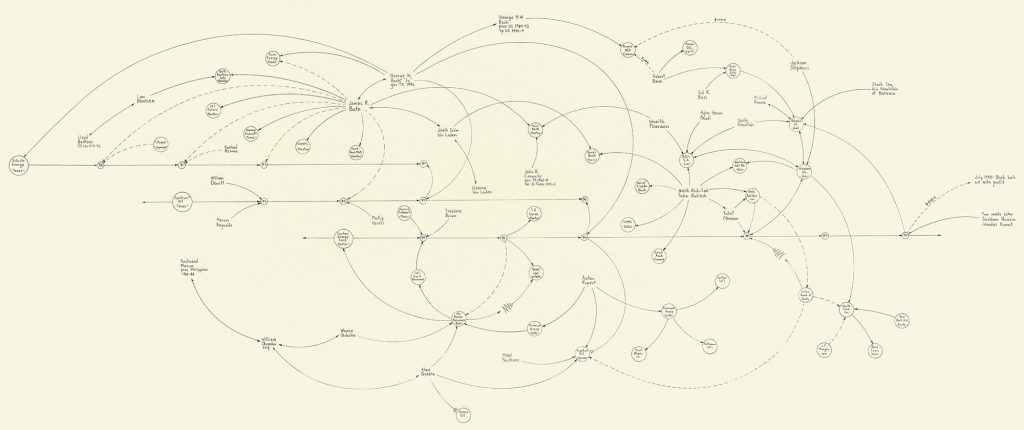

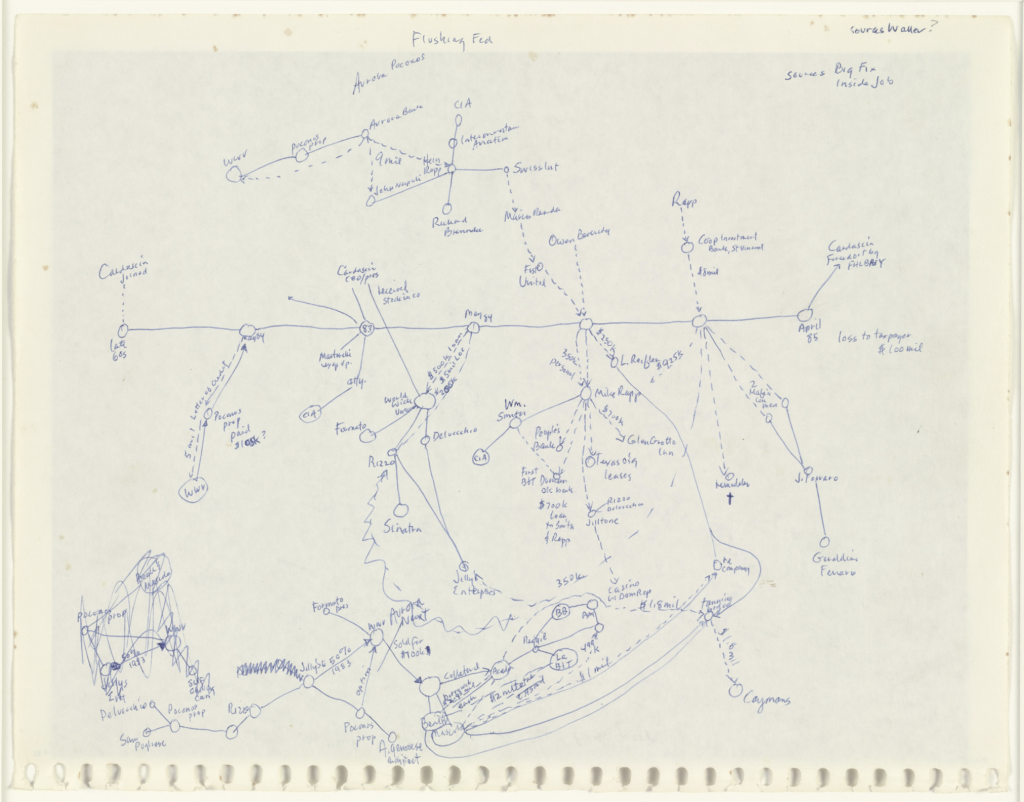

What is it that sparked the secret service’s interest in Lombardi and his work? In his artwork, Lombardi described what conspiracies and scandals such as the BCCI scandal consisted of. The mappings include important actors, corporations and other references, all done by hand. Originally, his work was ‘just’ a tool of support for him to make sense of all the index cards he kept of the scandals he researched. “He essentially drew ideas and not water lilies”, explains journalist Patricia Goldstone.

Goldstone, who wrote a biography about Lombardi (‘Interlock: Art, Conspiracy, and the Shadow Worlds of Mark Lombardi’), also refrains from what ultimately ended Lombardi’s life, stating: “His death leaves us with many questions, it is true. But any attempt of giving answers would be counterproductive.”

According to the journalist, the FBI, the CIA, the Department of Defense and the Office of Naval Research all studied the artist’s work in the wake of 9/11, a subject he covered in his drawings. But before his death, Lombardi might have sparked the interest of major players in the world of banking and politics.

He retained records that linked the Bush family together with Khaled bin Mahfouz for instance. After 9/11, suspicion fell on the Saudi financier that he and his family had funneled money to Al Qaeda. Allow us to point out something, here: the artist’s death took place during the presidential election.

After Lombardi’s death, art critic Jerry Salz wrote that he was more than a conceptualist or political artist:

“He’s a sorcerer whose drawings are crypto-mystical talismans or visual exorcisms meant to immobilize enemies, tap secret knowledge, summon power and expose demons. The demons Lombardi concerned himself with, however, weren’t otherworldly. He was after real people who were either hiding in plain sight or who had managed to fade into the woodwork. Lombardi was on a mission: He wanted to right wrongs by revealing them.”

Making connections

Journalist Goldstein, for a major part, does not discuss Lombardi’s death. Instead, she discusses his art:

“The world is defined by connections between various types of entities – individuals, companies, institutions, state organizations, etc. – and there is business involved, and there is big money involved. Ultimately, what Lombardi’s work shows us, is the intertwining of economy and politics. And what this leads to is the fact that politics is no longer the place for practicing political thought, but rather for implementing economic interests.”

It is exactly that that intrigues us about Lombardi’s work, which at first sight can be confusing and unorderly: the connections that he makes. Information in his art seems to be just that at first sight, but one plus one always turns out to be two when connections are made.

With the connections made, Lombardi reveals hidden information. It’s the connection that makes it critical. It screams ‘there’s more behind this’.

The right perspective

It all has to do with getting your head into a new perspective on things, if you think about it. With each perspective of different elements and actors that you take, you will see how the connections are more clearly.

The trick, in that sense, is to put yourself into the shoes of others. Why is it that X would choose to do Y? What are their motivations and what options do they have in the first place? And if that would happen, how would that affect others in turn?

Creating these connections between elements, as Lombardi does, can be called making an interlock. In the end, all of his works connect together like one massive interlock of information.

Goldstein describes it as such:

“Interlocks are basically a form of flowchart tracing overly cozy relationships between boards of directors. They’re common in accounting and in some forms of litigation, but they’re very, very unusual in the art world. Mark used interlocks to draw what amounts to a continual visual history of the interconnections between intelligence and organized crime and corporations and governments in the shadow banking industry.”

Exemplifying the connection

If Lombardi was alive today, perhaps he would be creating a mapping of the horrific war that’s taking place in Ukraine. Going over just a few news long reads, the political and economic interest of many, many people shines through. Imagine what would happen if we were to connect all of them in a map like Lombardi does.

Why is Germany for instance not withdrawing their energy imports from Russia straight away? As many news messages make clear, Russian and German economies are strongly intertwined, with Germany being largely dependent on the ex-Soviet nation for gas. However, how this dependency came to be is not easily explained, as a thousand factors come together.

Let’s take just one of those factors to see what we mean by that: the availability of gas in the neighboring country the Netherlands. More specifically, the province of Groningen (bordering Germany), houses a large source of gas that is being used for energy supplies. Why does Germany not switch to this source? Well, citizens of Groningen have battled for years to see the gas exploitation put to a halt, as their houses are breaking down due to earthquakes. This, in turn, has sparked large-scale political discussions as to how to proceed.

So, drawing lines from one to the other, somehow even earthquakes in a Dutch province can be linked to a war raging on the other side of the continent. You can imagine how many thousands of more connections can be made on this topic alone, let alone if you start connecting other major political events.

‘Aha!’ or metacognitive thinking

Making connections can often lead to an aha-moment. A normal life example: you have recently moved to a new city. You’re quite aware of your surrounding area. Think: how to go to the supermarket, where the nearest bus stop is. You’re also aware of an area a bit further away, because you like to go shopping for clothes there – by bus. On a sunny day, you decide to walk around your area until suddenly you find yourself in front of that one clothing shop you adore. Aha, this leads to here! The two maps that are in your head, are at once connected! Now, you feel like you know your new city ten times better.

That’s also how it is with learning and retaining knowledge. Making connections between what seem to be seperate pieces of information is extremely useful to get to know the world better – as Lombardi demonstrated too. This ‘taking a step back and seeing the bigger picture’ is called metacognitive thinking. In its basic form, it’s an awareness of one’s thought processes and an understanding of the patterns behind them.

Metacognitive thinking such as Lombardi does, is actually at the source of creativity. Another soul that comes to mind when we think ‘creativity’, pinpointed just that. Steve Jobs explained it loud and clear in this quote from a 1996 Wired interview:

“Creativity is just connecting things. When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel a little guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something. It seemed obvious to them after a while. That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things.”

That’s exactly what creativity is in its basic form, we believe too: making the right connections and seeing the bigger picture. Mark Lombardi clearly knew that, too.

Sources

- https://web.archive.org/web/20130517150914/http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P2-5081427.html

- https://www.moma.org/artists/22980

- https://whowhatwhy.org/podcast/the-mysterious-death-of-an-artist-whose-drawings-were-too-revealing/

- https://www.thedailybeast.com/the-artist-who-obsessed-the-fbi

- https://www.newsweek.com/2015/10/16/contemporary-artist-mark-lombardi-death-379532.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Lombardi

- https://nobaproject.com/blog/2019-11-06-metacognition-and-the-value-of-making-connections

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metacognition

Header image: Lianhao Qu